What makes virtual worlds successful?

Why some virtual worlds succeeded and survived for many years while more recent ones failed miserably

Artikel ansehen

How to add your Hubzilla channel to Fediverse.info

If you want to add your Hubzilla channel to the project-independent Fediverse People Directory at Fediverse.info, but you're struggling to get it submitted, here is a how-to which worked at least for me.

Step 0: Obviously, you have to have PubCrawl activated. Being on Fediverse.info is kind of senseless without PubCrawl because it's mostly for a Mastodon audience. If you don't want to have PubCrawl on, stop right here and rely on Hubzilla's own directories instead.

Step 1: Prepare your profile. If you've got multiple profiles, prepare your default profile. Edit it. Open the "Miscellaneous" tab.

There you have to edit the "About me" field. It's the equivalent of the self-description on Mastodon, so it'll be your Fediverse.info profile text. Describe yourself there.

At the bottom, add hashtags. Fediverse.info reads hashtags, but since it's built against Mastodon, it can't read Hubzilla's keyword field. It can only read hashtags from the "About me" field.

Most importantly: Add the hashtag #fedi22. Fediverse.info won't add your channel without it.

Step 2: Let the changes settle. Don't advance to the next step until at least 15 minutes later. Maybe do something else in the meantime. But don't forget what you were doing here.

Step 3: Go to the Fediverse.info directory page (see the link at the top).. Click on "Add Account". Go on and confirm that you've added #fedi22 to your profile. If you haven't, go back to step 1 and 2 and come back to step 3 later.

Step 4: Add your full channel URL. Only this works. Your Fediverse ID () does not, regardless of with or without a leading @, neither does your profile URL.

Step 5: Click Proceed.

You should get a message that includes the hashtags discovered in the "About me" field except for #fedi22. This means your channel has been added.

This method might also work with (streams), only that Fediverse.info doesn't know (streams), and most (streams) instances don't identify as "Streams" anyway.

Step 0: Obviously, you have to have PubCrawl activated. Being on Fediverse.info is kind of senseless without PubCrawl because it's mostly for a Mastodon audience. If you don't want to have PubCrawl on, stop right here and rely on Hubzilla's own directories instead.

Step 1: Prepare your profile. If you've got multiple profiles, prepare your default profile. Edit it. Open the "Miscellaneous" tab.

There you have to edit the "About me" field. It's the equivalent of the self-description on Mastodon, so it'll be your Fediverse.info profile text. Describe yourself there.

At the bottom, add hashtags. Fediverse.info reads hashtags, but since it's built against Mastodon, it can't read Hubzilla's keyword field. It can only read hashtags from the "About me" field.

Most importantly: Add the hashtag #fedi22. Fediverse.info won't add your channel without it.

Step 2: Let the changes settle. Don't advance to the next step until at least 15 minutes later. Maybe do something else in the meantime. But don't forget what you were doing here.

Step 3: Go to the Fediverse.info directory page (see the link at the top).. Click on "Add Account". Go on and confirm that you've added #fedi22 to your profile. If you haven't, go back to step 1 and 2 and come back to step 3 later.

Step 4: Add your full channel URL. Only this works. Your Fediverse ID () does not, regardless of with or without a leading @, neither does your profile URL.

Step 5: Click Proceed.

You should get a message that includes the hashtags discovered in the "About me" field except for #fedi22. This means your channel has been added.

This method might also work with (streams), only that Fediverse.info doesn't know (streams), and most (streams) instances don't identify as "Streams" anyway.

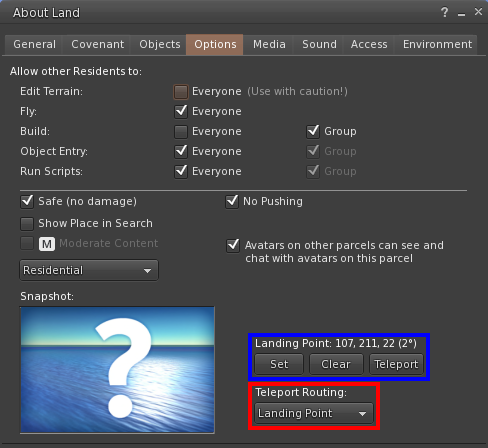

Image description for "How to configure landing points in Second Life and OpenSim"

Cropped screenshot of the "About Land" info and configuration dialogue window in the Firestorm Viewer.

The Firestorm Viewer is a viewer, a client, for Second Life and virtual worlds running OpenSimulator which is a free, open-source re-implementation of largely the same technology as Second Life. Firestorm is available for 32-bit and 64-bit Windows, 64-bit macOS and as an installable binary for 64-bit Linux, each of them in separate variants for Second Life and OpenSim. The dialogue window belongs to the Linux OpenSim version.

It displays information about the land that an avatar is on and, if the avatar has sufficient rights to do so, configure it to varying degrees. It is 488 pixels wide and 448 pixels high with slightly rounded top corners in front of a sky-blue background. It shows Firestorm's eponymous theme in its default Grey colour scheme which is mostly dark grey with very light grey writing in the Deja Vu Sans Book typeface.

The title bar has a vertical gradient from slightly lighter than the basic dark grey to basic dark grey itself. Towards the left end, the title "About Land" is written in a font that's slightly larger than that of the rest of the dialogue. Towards the right end, there are three buttons. From left to right, the first one is a question mark which opens a help page on the Firestorm Wiki, depending on which tab is selected. The second one is a short, thick horizontal line which minimises the dialogue to the top left corner of the in-world view in the viewer. The last one is an X-like cross which closes the window. From the rest of the dialogue window, the title bar is separated with a very dark grey horizontal line

Below the title bar and a bit of unused space showing only the grey background which is about half as high as the title bar, there is the tab bar with eight tabs arranged in one horizontal line: General, Covenant, Objects, Options, Media, Sound, Access, Environment. The background of the tabs is a slightly lighter vertical gradient from light to dark than the title bar. The Options tab is the only exception; as it is the active tab, it has a solid tan background. The tabs are separated from each other by vertical lines which give the impression of very narrow gaps. Immediately below the tab bar, a medium grey, one-pixel-high horizontal line leads almost all the way from one vertical edge of the dialogue window to the other one.

The upper section of the dialogue, below the title bar and taking up about 30% of the height of the dialogue window, controls the avatar permissions on the land. It starts with the writing, "Allow other Residents to:" which, in comparison to the rest of the dialogue below the title bar, is shifted further to the left, about 55 or 60% closer to the edge.

Five vertically aligned check boxes follow. They're all at about 40% of the width of the dialogue box from the left with their titles all the way to the left and extra writing which always reads or starts with "Everybody" almost immediately to the right. The lower three have a secondary check box at about 65% of the width of the dialogue with "Group" written almost immediately to their own right. The "Everybody" check boxes grant the respective permission to all avatars on the land. The "Group" check boxes only grant them to avatars that are members of the group which is associated with the land, if any.

The first check box is labelled, "Edit Terrain:" It is unchecked. Next to the writing "Everyone" to its right, "(Use with caution!)" is written in the same hue of medium grey as the line below the tab bar. This parameter controls whether only the land owner or everyone may raise or lower the ground or change its texture. In most cases, having it checked is not recommended because everyone could mess with the land as they please.

The second check box is labelled, "Fly:" It is checked. When enabled, all avatars are allowed to start flying on the land. There can be many reasons for disallowing it. One would be because flying breaks the immersion and thus disturbs the land owner. This particularly applies to role-play sims. Another one would be because there is a parcours on the land, and flying would be cheating. Yet another one would be because the land owner doesn't want others to reach a secret platform high up in the sky. However, flying being disallowed has its own disadvantages. It could make a sim very hard to navigate if the owner hasn't taken particular care of making it navigable by paths and bridges, by teleporters, by vehicles or whatever. It also makes swimming in the water without scripts impossible as well as getting out of the water if the shore can't simply be walked up.

The third pair of check boxes is labelled, "Build:" The "Everyone" check box is unchecked, the "Group" check box is checked. These check boxes enable avatars to rez objects, that is, put objects on the land, regardless of whether they come from the inventory or whether they're being newly created. In most cases, it is not wise to let everyone build and rez on the land unless it's a sandbox. Sometimes it makes sense to have a small parcel where objects can be rezzed, for example for boats on a boating sim or for sales boxes on a shopping sim to unpack them. Still, there is always the risk of squatters or griefers misusing building rights.

The fourth pair of check boxes is labelled, "Object Entry:" Both check boxes are checked, and as "Everyone" is checked, "Group" is greyed out. Object entry refers to the permission to move objects which already exist in-world onto this land. This is usually safe if there is no land anywhere nearby where griefers could rez objects. Also, it is required to enter the land in a vehicle such as a boat.

The fifth pair of check boxes is labelled, "Run Scripts:" Both check boxes are checked, and as "Everyone" is checked, "Group" is greyed out. This option controls whether avatars are allowed to run scripts in objects attached to them. While disallowing scripts lowers the impact of avatars on the server performance and eliminates some more attack vectors for griefers, it has a number of unpleasant side-effects. I've written a post about them.

Another horizontal line follows further below, this time in a hue of grey that is slightly darker than the text. It starts at the same distance from the left-hand edge as almost all the other objects in the dialogue that are aligned to the left, and it ends at the same distance from the right-hand edge. It is much closer to the objects below it than to those above it.

Below this line, there are two single check boxes, both of which are checked. The one to the left has the writing, "Safe (no damage)" to its right at the same distance as all other check boxes. If this check box is off, the avatar health system is activated which is mostly useful for combat in role-play. If the health of an avatar drops to zero, the avatar is teleported to its home.

The one in the middle has the writing, "No Pushing" to its right. It makes avatars pass through each other instead of colliding. If it is off, avatars can push other avatars around by bumping into them.

At a small distance below the "Safe (no damage)" check box, there is a check box with "Show Place in Search" written to its right. It is unchecked. If it was checked, the location would be discoverable through the search built into the various viewers. Also, the check box right below would not be greyed out. It is labelled with a dark grey M on a rounded white rectangle and "Moderate Content". This check box raises the rating to Moderate if the rating of the sim itself is only General. Both Second Life and OpenSim have three content ratings, the highest one being Adult. While they are mostly intended as content warnings, they also serve to keep underage users out on Second Life which, unlike OpenSim, has user age confirmation.

Below these two check boxes, there is a list box with which can be chosen under which category the location can be found. The following 14 categories are available:

- Linden Location (the name refers to Linden Labs, the creator, owner and operator of Second Life, and while doesn't make much sense in OpenSim, it is still available)

- Adult

- Arts & Culture

- Business

- Educational

- Gaming

- Hangout

- Newcomer Friendly

- Parks & Nature

- Residential

- Shopping

- Stage

- Other

- Rental

Further below, there is an embossed rectangular area labelled, "Snapshot:" which would contain an image that would represent the location. In this case, no image has been assigned to it, so the default placeholder is shown instead. It shows a blue ocean with wave ripple on it that gets much darker very close to the horizon. The sky above the horizon shows a gradient from gives an impression of a sunrise or sunset with no celestial body to be seen. Nonetheless, there is a white reflection on the right-hand half of the visible piece of ocean that suggests a large, bright celestial body where there is none in the sky. In the foreground, right in the middle of the image, there is a large white question mark in a bold typeface which is surrounded by some about-two-pixels-wide shading. The whole image, minus the question mark, shows some significant vignetting which makes it darker towards all four edges.

In the middle again, roughly below the "No Pushing" check box with a small shift to the right, about one third of the height of one check box lower than the "Moderate Content" check box, there is the last check box of the dialogue. It is labelled, "Avatars on other parcels can see and chat with avatars on this parcel", and it is checked. This renders avatars on this particular land visible to avatars outside the land, and if they're close enough, they can also read what the avatars on this land post to the local chat.

To the right of the snapshot area, there are the controls which the article is about. They define the landing point of avatars that teleport onto this land.

The upper part of these controls was marked by me with a blue rectangle. There is the label, "Landing point:" followed by the landing point coordinates: 107 metres from the western edge of the sim, 211 metres from the southern edge of the sim, avatar centre 22 metres above zero which means two metres above default water line, 2 degrees rotated counter-clockwise from facing straight northward.

Below that, there are three buttons. The first one is labelled, "Set". It sets the coordinates to where the avatar is currently standing and facing. The second one is labelled, "Clear". It clears the entered landing-point.

The lower part of these controls was marked by my with a red rectangle. It starts with the label, "Teleport Routing:" Below the label, there is a list box that offers the options "Blocked", "Landing Point" and "Anywhere". It is set to "Landing Point".

What these controls do exactly and how it influences where avatars land after teleporting is described in detail in the article which this image description belongs to.

Finally, there is another horizontal line near the bottom edge of the dialogue window which is as long as the one lining the tab bar. It is very dark grey.

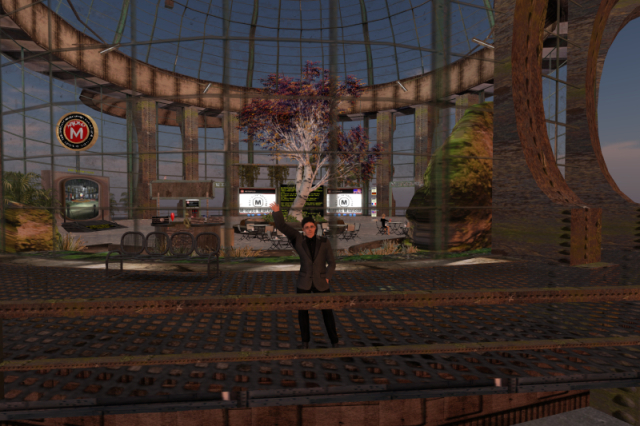

Description of this image as announced in this thread:

My avatar in the Metropolis Metaversum, waving good-bye at the on-looker from the Metropolis welcome building before Metropolis shuts down for good.

The Metropolis Metaversum, Metropolis or Metro in short, was a virtual 3-D world, also referred to as a grid in this context, based on OpenSimulator which is a free and open-source server-side re-implementation of Second Life. It was one of the earliest OpenSim grids and the first one run by Germans, and it was shut down by its owners on July 5th, 2022 between 10:00 and 11:00 AM CEST after 14 years of operation.

The avatar is a light-skinned, dark-haired male adult wearing metal-framed glasses, a dark grey blazer jacket with darker grey shoulders and collar which is buttoned up, a black button-down shirt buttoned up all the way to the collar, a pair of dark black denim jeans and a pair of black full-brogue shoes.

He is standing on the outside platform of level 3, the top level of the building and waving his right hand while having his left hand on his hip. The floor of the platform is standing on the outside platform of level 3, the top level of the building out of four levels altogether. It was also the place where both new avatars appeared for the first time and travellers landed when teleporting in.

The floor is a rusty steel girder that's so coarse that it'd be fairly hard to walk on in real life; here it is only a semi-transparent texture on a solid surface. In front of the avatar is the double railing made of likewise rusty steel that surrounds the platform. Below the platform, the rust-coated structure that carries level 3 can be seen.

Level 3 itself, entirely behind the avatar with the exception of the outside platform, is encased in a glass cupola with a cylindrical lower part and a spherical upper part, both with semi-transparent green reinforcements between what would otherwise appear as single glass panes. The spherical upper part rests on a support ring made of sheet metal panels with rusty outer edges. This ring, in turn, is carried by four triple sets of boxy, rusty steel columns with semi-elliptical cutouts on the far side of the cupola that roughly give the impression of being riveted. One triple set of columns can be seen right outside the cupola to the right of the avatar, another two can be seen in the background to the left and to the right of the avatar.

Within each triple set except the one in the front to the right, there are two passageways into the cupola. Each passageway is surrounded by a greenish metal frame; each pair of these frames carries the marquee "METROPOLIS GRID" made of light grey concrete with blinking white lightbulbs on it on the inside.

A circular structure made of rusty steel pipes is mounted on the inside of the support ring and carries a number of neon lights with rusty sheet metal covers above them. A semi-circular structure made of likewise rusty sheet metal protrudes outward from the support ring above the two columns to the left in the background.

To the left of the avatar and on the front part of the platform, there is a dark grey four-seat bench made of rounded square steel tubes with fine steel girders in them as legs, seats and backrests.

Around the inside of the cupola, there is a narrow strip with a plant-like green and greyish brown texture going all around except for the passageways. The floor inside the cupola gives the impression of cracked grey concrete.

On the left-hand edge of the picture and behind the front set of support columns, there are two greyish-brown rocks with green moss on top; the one behind the columns is almost twice as tall as the one to the left.

Also inside the cupola, behind the four-seat bench, there is the circular info desk with a sign mounted on top and an NPC modelled after the robot Maria from Fritz Lang's 1928 silent movie Metropolis standing on the inside of the desk. Unlike Second Life, OpenSim allows for actual, scriptable NPCs that don't need a running viewer to appear in-world. This NPC, named Bertha, has even basic chatbot functionality implemented.

The sign above the info desk is made from rusty sheet metal, a surrounding frame made of zinc-coated steel tubes which still show some rust and two bamboo poles as supports which are stuck through the bottom horizontal pipe. It can only be seen from behind in this picture. A small red and light brown bird is perched on top of the sign.

What gives the impression of promotional material for both the film and the grid is placed on the counter top of the info desk, the visible face showing Maria's head and the writing "Metropolis Metaversum", as are a red and white strawberry cocktail and a light grey laptop computer with a brushed aluminium case that has a static image of a Windows desktop with the start menu open amongst other things as its screen texture. The red object above the counter top to the left of the NPC is a heart slowly rotating clockwise which provides access to the avatar-partnering feature.

An artificial pond with various plants in it extends from behind the info desk past the front of the larger rock to the next passageway.

To the left of the info desk, there's the walk-in teleporter that leads down to level 2. It mimicks the look of an old CRT screen of enormous size, built into a weathered metal casing with a low dark grey ramp in front of it. The screen on the teleporter shows a part of level 2 with its green floor, dark grey walls and several more teleporters in front of these walls. The yellow writing "Grid Teleport Center" is hovering above the teleporter. On the ramp to the teleporter, there is a black sign that reads, "Wenn Durchgehen nicht klappt, Klicken Sie das Bild zum Teleportieren. When Walk-Through does not work, Click the Image to teleport."

A zinc-coated but slightly rusty metal pipe on top of the teleporter that slowly rotates counter-clockwise carries a special Metropolis sign. The inner part is red with the logo of the film Metropolis and the capital letter M on it, both in white. It is surrounded by a brass ring that separates it from a black area which has more writing in white on it: "DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF FREE VIRTUAL WORLDS" above centre, "METROPOLIS METAVERSUM" below centre and one five-prong star on each side separating the two writings. The outside is another brass ring.

The column between the passageways in the background to the left carries a black sign with group joiners for the Metropolis Newsnet group. The sign has the octagonal red Metropolis logo with a white M in the middle and a white edge around it in the top left corner. To the right of the logo, it is labelled in white, "Metropolis Newsnet Gruppe" which is partly German and translates to "Metropolis Newsnet Group". The writing below reads, "Aktuelle Informationen um Metropolis" and "Ankündigungen, Infos, Events, Fragen und Antworten im Chat" which is mostly German and translates to "Announcements, infos, events, questions and answers in the chat". The small neon green writing at the bottom edge reads, "Klick hier und folge dem Link im allgemeinen Chat, um der Gruppe beizutreten. Im Gruppenfenster JOIN klicken.(Click here to join the Metropolis Newsnet group." The German part of this translates to, "Click here and follow the link in the general chat to join the group. In the group window, click JOIN." Right below the black sign are three clickable white panels with black writings on them, "deutsch", "français" and "english".

A black box with a red top and on each side a large red M and the small red writing "Translator" which contains the Metropolis Translator is offered on a small round red table below the group joiners. The translator is one out of many which automatically translates whatever the user posts in the public chat into another language.

Above the black sign, the lower edge of another sign that lists the Metropolis core team is visible; the rest of the sign is covered by the sign above the info desk.

There is a round concrete structure in the middle of the floor which serves as seating and as a planter for an ash tree with white bark and yellowish and reddish autumn leaves that has grown up to the support ring plus four small green bushes around it.

Four tables with four chairs each, all made of iron painted black plus light brown wooden planks and foldable, are placed irregularly in front of the circular structure with the ash tree. All the way to the right, a blond woman in a black short-sleeved minidress is sitting at one of the tables with another identical strawberry cocktail in front of her. She is a static, unscripted model of Bertha Senior, the former Metropolis greeter.

Right behind the ash tree, there is a black sign with yellow writing on it which announces the unofficial Metropolis farewell party in this location on level 1, two levels further down, in the evening of June 30th which was scheduled to be the last day of Metro's operation. The sign was written in German by the Dutch Metropolis tech admin Neovo Geesink who had installed it only a few days before June 30th, and it reads, "Am Donnerstag der 30. Juni gibt es hier im Metro, Region "*Metropolis*", UND im OSGrid, Region "Metro Memoriam" eine EndParty für das Metropolis Grid. Es startet am 21:00 Uhr Lokalzeit. (12:00 PDT) DJ LadyJo werde am Stream gehen und der Party Hosten. Im "Metro Memoriam" ist auch eine Memoriam / Erdenkungs ort zur Metropolis Hergestellt. Wenn Unvorsehen der Metro bereits Runter gegangen ist, werde der Party jedoch im OSGrid am "Metro Memoriam" statt haben. HG adresse für die Karte nach der Region im OSGrid: hg.osgrid.org:80:Metro Memoriam Oder klicken Sie diese Tafel an um direkt zu Teleportieren. Neovo Geesink."

This translates to, "On Thursday, June 30th, there is a party to celebrate the end of the Metropolis Grid here in Metro, region "*Metropolis*", AND in OSgrid, Region "Metro Memoriam". It starts at 21:00 local time. (12:00 PDT) DJ LadyJo will enter the stream and host the party. Also, at "Metro Memoriam", a memorial/remembrance place for Metro has been created. If Metro has been shut down unexpectedly, the party will still take place in OSgrid at "Metro Memoriam". HG address for the map to the region in OSgrid: hg.osgrid.org:80:Metro Memoriam Or click the panel to teleport directly. Neovo Geesink."

The sign doubles as a clickable teleporter to a memorial sim which had been built on another grid, OSgrid, and which hosted the Metropolis farewell party in parallel with the club on level 1 of the Metropolis welcome building. Two timezones are mentioned; one is CEST which is local time for Germany, home of the grid, and the other one is PDT which is official grid time in both Second Life and all OpenSimulator-based grids.

Two screens are on the sides of this black sign, hanging on two stainless steel chains each, both with five blue buttons below them for navigation. Both screens allow avatars to navigate through nine pages. They are both on the last page. The screen to the left offers basic information about Metropolis in German, the one to the right does the same in English. Both screens show black bars at the top. The black bars have the octogonal, red and white Metropolis logo to the left with "METROPOLIS" written next to it. In addition, the screen to the right has a combined flag on the right end of the black bar, the top left half of which is the U.S. flag, but with only 25 stars, and the bottom right half is the British flag. The rest of both screens is white with a variation on the octagonal Metropolis logo, now in black and semi-transparent, surrounded by the arched black writing "MEA*VITA*CREATIVUM" which is Latin for "my creative life" and with a black "METROPOLIS METAVERSUM" writing below it.

Another circular segment of steel girder is mounted above the screens, and ivy is hanging down from it.

Between the screen to the right and the one of the passageways further to the right stands a truss made of zinc-coated steel with four vertical pipes in a square arrangement which carries three support request signs and online indicators for support staff. All three have a dark blue "SUPPORT?" label at the top. The top one is in German with "Du hast Fragen oder brauchst Hilfe?" ("You have questions or need help?") written on it in black and "HIER KLICKEN" ("Click here") written below in green and the German flag at the bottom. The middle one is in French with "Vous avez des questions? Vous avez besoin d'aide?" ("You have questions? You are in need of help?") written below in black, "Cliquez ici" ("Click here") written further below in black and the French flag at the bottom. The bottom one is in English with the combined American and British flag in the middle, "Do you have any questions or do you need help?" written below in black and "CLICK HERE" written at the bottom.

Additional vegetation includes ferns in rotund, rusty vases both inside and outside the cupola, including one to the left and two to the right of the teleporter, and potted bamboo outside to the left of the teleporter.

The light is subdued because the sun was permanently set to sunset on the welcome sim, just like on all other official sims throughout the grid, during the last days of Metropolis.

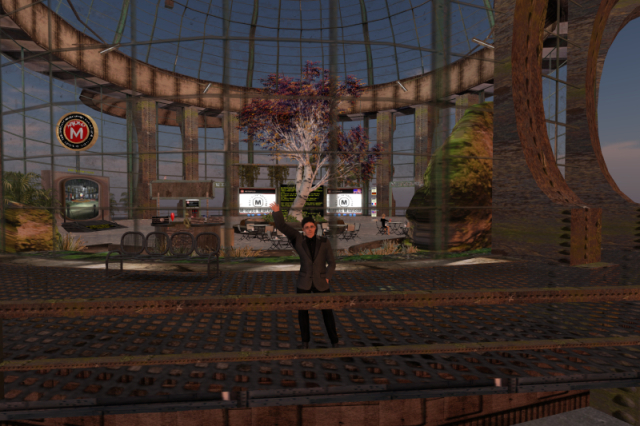

My avatar in the Metropolis Metaversum, waving good-bye at the on-looker from the Metropolis welcome building before Metropolis shuts down for good.

The Metropolis Metaversum, Metropolis or Metro in short, was a virtual 3-D world, also referred to as a grid in this context, based on OpenSimulator which is a free and open-source server-side re-implementation of Second Life. It was one of the earliest OpenSim grids and the first one run by Germans, and it was shut down by its owners on July 5th, 2022 between 10:00 and 11:00 AM CEST after 14 years of operation.

The avatar is a light-skinned, dark-haired male adult wearing metal-framed glasses, a dark grey blazer jacket with darker grey shoulders and collar which is buttoned up, a black button-down shirt buttoned up all the way to the collar, a pair of dark black denim jeans and a pair of black full-brogue shoes.

He is standing on the outside platform of level 3, the top level of the building and waving his right hand while having his left hand on his hip. The floor of the platform is standing on the outside platform of level 3, the top level of the building out of four levels altogether. It was also the place where both new avatars appeared for the first time and travellers landed when teleporting in.

The floor is a rusty steel girder that's so coarse that it'd be fairly hard to walk on in real life; here it is only a semi-transparent texture on a solid surface. In front of the avatar is the double railing made of likewise rusty steel that surrounds the platform. Below the platform, the rust-coated structure that carries level 3 can be seen.

Level 3 itself, entirely behind the avatar with the exception of the outside platform, is encased in a glass cupola with a cylindrical lower part and a spherical upper part, both with semi-transparent green reinforcements between what would otherwise appear as single glass panes. The spherical upper part rests on a support ring made of sheet metal panels with rusty outer edges. This ring, in turn, is carried by four triple sets of boxy, rusty steel columns with semi-elliptical cutouts on the far side of the cupola that roughly give the impression of being riveted. One triple set of columns can be seen right outside the cupola to the right of the avatar, another two can be seen in the background to the left and to the right of the avatar.

Within each triple set except the one in the front to the right, there are two passageways into the cupola. Each passageway is surrounded by a greenish metal frame; each pair of these frames carries the marquee "METROPOLIS GRID" made of light grey concrete with blinking white lightbulbs on it on the inside.

A circular structure made of rusty steel pipes is mounted on the inside of the support ring and carries a number of neon lights with rusty sheet metal covers above them. A semi-circular structure made of likewise rusty sheet metal protrudes outward from the support ring above the two columns to the left in the background.

To the left of the avatar and on the front part of the platform, there is a dark grey four-seat bench made of rounded square steel tubes with fine steel girders in them as legs, seats and backrests.

Around the inside of the cupola, there is a narrow strip with a plant-like green and greyish brown texture going all around except for the passageways. The floor inside the cupola gives the impression of cracked grey concrete.

On the left-hand edge of the picture and behind the front set of support columns, there are two greyish-brown rocks with green moss on top; the one behind the columns is almost twice as tall as the one to the left.

Also inside the cupola, behind the four-seat bench, there is the circular info desk with a sign mounted on top and an NPC modelled after the robot Maria from Fritz Lang's 1928 silent movie Metropolis standing on the inside of the desk. Unlike Second Life, OpenSim allows for actual, scriptable NPCs that don't need a running viewer to appear in-world. This NPC, named Bertha, has even basic chatbot functionality implemented.

The sign above the info desk is made from rusty sheet metal, a surrounding frame made of zinc-coated steel tubes which still show some rust and two bamboo poles as supports which are stuck through the bottom horizontal pipe. It can only be seen from behind in this picture. A small red and light brown bird is perched on top of the sign.

What gives the impression of promotional material for both the film and the grid is placed on the counter top of the info desk, the visible face showing Maria's head and the writing "Metropolis Metaversum", as are a red and white strawberry cocktail and a light grey laptop computer with a brushed aluminium case that has a static image of a Windows desktop with the start menu open amongst other things as its screen texture. The red object above the counter top to the left of the NPC is a heart slowly rotating clockwise which provides access to the avatar-partnering feature.

An artificial pond with various plants in it extends from behind the info desk past the front of the larger rock to the next passageway.

To the left of the info desk, there's the walk-in teleporter that leads down to level 2. It mimicks the look of an old CRT screen of enormous size, built into a weathered metal casing with a low dark grey ramp in front of it. The screen on the teleporter shows a part of level 2 with its green floor, dark grey walls and several more teleporters in front of these walls. The yellow writing "Grid Teleport Center" is hovering above the teleporter. On the ramp to the teleporter, there is a black sign that reads, "Wenn Durchgehen nicht klappt, Klicken Sie das Bild zum Teleportieren. When Walk-Through does not work, Click the Image to teleport."

A zinc-coated but slightly rusty metal pipe on top of the teleporter that slowly rotates counter-clockwise carries a special Metropolis sign. The inner part is red with the logo of the film Metropolis and the capital letter M on it, both in white. It is surrounded by a brass ring that separates it from a black area which has more writing in white on it: "DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF FREE VIRTUAL WORLDS" above centre, "METROPOLIS METAVERSUM" below centre and one five-prong star on each side separating the two writings. The outside is another brass ring.

The column between the passageways in the background to the left carries a black sign with group joiners for the Metropolis Newsnet group. The sign has the octagonal red Metropolis logo with a white M in the middle and a white edge around it in the top left corner. To the right of the logo, it is labelled in white, "Metropolis Newsnet Gruppe" which is partly German and translates to "Metropolis Newsnet Group". The writing below reads, "Aktuelle Informationen um Metropolis" and "Ankündigungen, Infos, Events, Fragen und Antworten im Chat" which is mostly German and translates to "Announcements, infos, events, questions and answers in the chat". The small neon green writing at the bottom edge reads, "Klick hier und folge dem Link im allgemeinen Chat, um der Gruppe beizutreten. Im Gruppenfenster JOIN klicken.(Click here to join the Metropolis Newsnet group." The German part of this translates to, "Click here and follow the link in the general chat to join the group. In the group window, click JOIN." Right below the black sign are three clickable white panels with black writings on them, "deutsch", "français" and "english".

A black box with a red top and on each side a large red M and the small red writing "Translator" which contains the Metropolis Translator is offered on a small round red table below the group joiners. The translator is one out of many which automatically translates whatever the user posts in the public chat into another language.

Above the black sign, the lower edge of another sign that lists the Metropolis core team is visible; the rest of the sign is covered by the sign above the info desk.

There is a round concrete structure in the middle of the floor which serves as seating and as a planter for an ash tree with white bark and yellowish and reddish autumn leaves that has grown up to the support ring plus four small green bushes around it.

Four tables with four chairs each, all made of iron painted black plus light brown wooden planks and foldable, are placed irregularly in front of the circular structure with the ash tree. All the way to the right, a blond woman in a black short-sleeved minidress is sitting at one of the tables with another identical strawberry cocktail in front of her. She is a static, unscripted model of Bertha Senior, the former Metropolis greeter.

Right behind the ash tree, there is a black sign with yellow writing on it which announces the unofficial Metropolis farewell party in this location on level 1, two levels further down, in the evening of June 30th which was scheduled to be the last day of Metro's operation. The sign was written in German by the Dutch Metropolis tech admin Neovo Geesink who had installed it only a few days before June 30th, and it reads, "Am Donnerstag der 30. Juni gibt es hier im Metro, Region "*Metropolis*", UND im OSGrid, Region "Metro Memoriam" eine EndParty für das Metropolis Grid. Es startet am 21:00 Uhr Lokalzeit. (12:00 PDT) DJ LadyJo werde am Stream gehen und der Party Hosten. Im "Metro Memoriam" ist auch eine Memoriam / Erdenkungs ort zur Metropolis Hergestellt. Wenn Unvorsehen der Metro bereits Runter gegangen ist, werde der Party jedoch im OSGrid am "Metro Memoriam" statt haben. HG adresse für die Karte nach der Region im OSGrid: hg.osgrid.org:80:Metro Memoriam Oder klicken Sie diese Tafel an um direkt zu Teleportieren. Neovo Geesink."

This translates to, "On Thursday, June 30th, there is a party to celebrate the end of the Metropolis Grid here in Metro, region "*Metropolis*", AND in OSgrid, Region "Metro Memoriam". It starts at 21:00 local time. (12:00 PDT) DJ LadyJo will enter the stream and host the party. Also, at "Metro Memoriam", a memorial/remembrance place for Metro has been created. If Metro has been shut down unexpectedly, the party will still take place in OSgrid at "Metro Memoriam". HG address for the map to the region in OSgrid: hg.osgrid.org:80:Metro Memoriam Or click the panel to teleport directly. Neovo Geesink."

The sign doubles as a clickable teleporter to a memorial sim which had been built on another grid, OSgrid, and which hosted the Metropolis farewell party in parallel with the club on level 1 of the Metropolis welcome building. Two timezones are mentioned; one is CEST which is local time for Germany, home of the grid, and the other one is PDT which is official grid time in both Second Life and all OpenSimulator-based grids.

Two screens are on the sides of this black sign, hanging on two stainless steel chains each, both with five blue buttons below them for navigation. Both screens allow avatars to navigate through nine pages. They are both on the last page. The screen to the left offers basic information about Metropolis in German, the one to the right does the same in English. Both screens show black bars at the top. The black bars have the octogonal, red and white Metropolis logo to the left with "METROPOLIS" written next to it. In addition, the screen to the right has a combined flag on the right end of the black bar, the top left half of which is the U.S. flag, but with only 25 stars, and the bottom right half is the British flag. The rest of both screens is white with a variation on the octagonal Metropolis logo, now in black and semi-transparent, surrounded by the arched black writing "MEA*VITA*CREATIVUM" which is Latin for "my creative life" and with a black "METROPOLIS METAVERSUM" writing below it.

Another circular segment of steel girder is mounted above the screens, and ivy is hanging down from it.

Between the screen to the right and the one of the passageways further to the right stands a truss made of zinc-coated steel with four vertical pipes in a square arrangement which carries three support request signs and online indicators for support staff. All three have a dark blue "SUPPORT?" label at the top. The top one is in German with "Du hast Fragen oder brauchst Hilfe?" ("You have questions or need help?") written on it in black and "HIER KLICKEN" ("Click here") written below in green and the German flag at the bottom. The middle one is in French with "Vous avez des questions? Vous avez besoin d'aide?" ("You have questions? You are in need of help?") written below in black, "Cliquez ici" ("Click here") written further below in black and the French flag at the bottom. The bottom one is in English with the combined American and British flag in the middle, "Do you have any questions or do you need help?" written below in black and "CLICK HERE" written at the bottom.

Additional vegetation includes ferns in rotund, rusty vases both inside and outside the cupola, including one to the left and two to the right of the teleporter, and potted bamboo outside to the left of the teleporter.

The light is subdued because the sun was permanently set to sunset on the welcome sim, just like on all other official sims throughout the grid, during the last days of Metropolis.

One year of Eternal November: The good, the bad and the ugly

What happened in the Fediverse and to the Fediverse since Musk bought out Twitter

Artikel ansehen

How to configure landing points in Second Life and OpenSim

An explanation for the landing point controls and how to make landing points act the way you want them to

Artikel ansehen