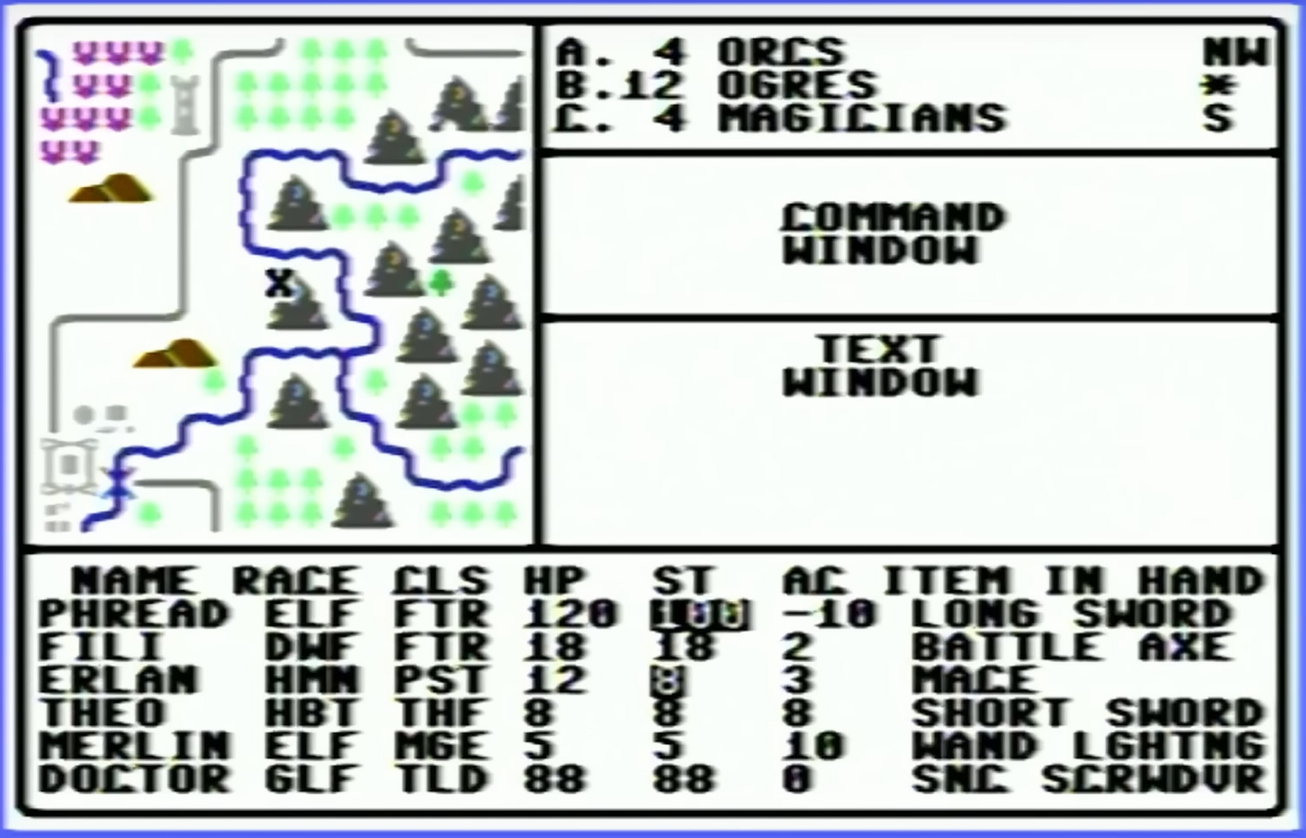

Luckily, Stephen’s younger self went to some extremes documenting the project, starting with a map he created which was inspired by Dungeons and Dragons. There are printed notes from a Commodore 64 printer, including all the assembly instructions, augmented with his handwritten notes to explain how everything worked. He also has handwritten notes including character set plans, disk sector use plans, menus, player commands, character stats and equipment, all saved on paper. The early code was written using a machine language monitor, since [Stephen] didn’t know about the existence of assemblers at the time. Eventually he discovered them, attempted to rebuild the code on a Commodore 128 and then an Amiga, but never got everything working together. There is some working code still on floppy disk, but a lot of it doesn’t work together either.

Goes to show again the value of printing on paper for long term storage. I experienced the same thing when I wanted to resuscitate a program I'd written on the HP-41CV about 35 years ago. I'd also kept all my handwritten notes, and with a few fixes, I got it going again, and I published the code on Github. I also remember having printed out and filing all the Clipper source code that I worked on in my professional career in the 1990's - more because we filed everything, and not because I was specifically thinking about the longevity of it being accessible.

See

Well Documented Code Helps Revive Decades-Old Commodore Project#

technology #

Commodore64 #

gaming #

archiving

In the 1980s, [Stephen] was working on his own RPG for the Commodore 64, inspired by dungeon crawlers of the era like Ultima IV and Telengard, both some of his favorites. The mechanics and gameplay…